This is the third of our instructor-led online discussions for Mu 101 (Spring 2020). Refer to the handout you received the first day of class (click on this highlighted text to go to that page our class website) which describes the amount and kinds of contributions you’re expected to make to these online discussions (adding your own ideas, responding to others’ ideas, and asking questions that others can respond to) — these are all the same parameters of good conversation that happens offline, too!

The most effective comments in an online forum are short — think about how you skim past others’ comments if they’re more than a couple lines long instead of engaging closely with that person’s ideas! If everyone involved in these weekly conversations only posts a single long comment, it won’t be a conversation, and we won’t all benefit from opportunity to learn from each other. Rather than dropping in on the blog once during the week and adding a single long comment, think of this forum as an opportunity to have a conversation with your fellow classmates. A conversation, whether online or in person, involves back-and-forth contributions from everyone involved: adding something new based on your own experiences or ideas, asking questions, responding to the ideas of others. The best way to get the most out of this learning experience is to share your single best idea, give room for others to respond, and then build on each others’ contributions later in the week.

The reading time of this post is approximately 13 minutes, not including links to additional materials. There are a few questions at the end of the post that can get the discussion going (there’s no need to respond to all of them or even any of them directly—they’re just a suggestion for getting started, and you may find it helpful to read them first before reading the rest of the post).

Cycles of history

Most aspects of music—how it’s made, how it’s consumed, what sounds people prefer, how it’s performed, and how it’s learned—progress in cycles throughout history from being popular/affordable/accessible to being elite/costly/niche and back again. Put another way, aspects of music that were popular in one generation or century are the same features that will be considered elite or rare in the next. As cultural norms, wealth, and social needs shift over time, music changes, too. So, the history of music can be an indicator of other broad trends in history, economics, politics, and social structure.

As you read, think about other history courses you’ve taken that help fill in the gaps in this chronological survey. Think, too, about the ways in which this survey reinforces what you’ve learned in school or from reading (literature and non-fiction!) and movies—every piece of information we add helps flesh out your sense of the world and all it contains.

There’s one constant about how music is learned to keep in mind throughout this historical survey. As long as music has existed—and this is true today, as well—people have learned to make music by listening to music that’s already been made and by trying their hand at making music with each other. The skills, techniques, and details of music are passed down directly from an older group of musicians to a younger group.

Ancient Greece and the Medieval period (ca. 12th century BC to 1400 AD)

For a large portion of European history, the keepers of knowledge were monks and nuns. In between prayers (we’ve heard examples of the prayers they would sing in class) and chores (e.g., cleaning, feeding animals, farming), a common daily task for men in a monastery or women in a nunnery was creating copies of important texts by hand. These texts included religious treatises, scientific texts, Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, and music.

The history of how music was learned is also the history of how people thought about music. One of the most important takeaways when thinking about music in the Medieval period is knowing just how important music was in the whole spectrum of human knowledge. The way people thought about education was quite different than it is now, and people divided human knowledge into two groups of related subjects, the quadrivium and the trivium:

| Trivium (Literary arts) | Quadrivium (Mathematical disciplines) |

|

|

Together, all seven subjects constituted a complete liberal arts education, and mastery of the trivium was required before taking on the quadrivium. Notice where music is placed—it’s of equal importance with math and the sciences. Notice, too, that none of the other fine arts appear anywhere in this list of essential subjects.

Organizing and prioritizing human knowledge in this way is an idea that comes from Ancient Greek philosophy. Here are some examples of how people thought about knowledge and music:

“Music is a science, certainly, in which exists sure and infallible knowledge.” —Aristides Quintilianus, On Music (ca. 130 AD)

“[T]he cosmos is ordered in accord with harmonia (just as the disciples of Pythagoras assert) and we need the musical theorems for the understanding of the whole universe.. [and] certain types of melos [melody, rhythm, and words sung] form the ethos of the soul.” —Sextus Empiricus, Against the Musicians (2nd century)

“Plato said, not idly, that the soul of the universe is united by musical concord [consonance]… [T]he music of the universe is especially to be studied in the combining of the elements and the variety of the seasons which are observed in the heavens. How indeed could the swift mechanism of the sky move silently in its course? And although the sound does not reach our ears, the extremely rapid motion of such great bodies could not be altogether silent, especially since the courses of the stars are joined together by such mutual adaptation that nothing more equally compacted or united could be imagined. For some orbit higher and others lower, and all revolve by a common impulse, so that an established order of their circuits can be deduced from their various inequalities. For this reason an established order of modulation [i.e., music with a mathematical connotation] cannot be lacking in this celestial revolution.” —Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, Fundamentals of Music, Book I (ca. 500), a summary of the works of Nichomachus (60-100) and Ptolemy (100-168)

There are many ways that the works of Greek thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Epicurus, Euripides, and Socrates continue to shape the world in which we live today—democracy, trial by jury, empirical scientific observations, and public theater all come from Ancient Greece, for example. The very assumption that music is an important thing to study—something that Europeans have believed for thousands of years, long after the quadrivium was abandoned in education, to the point that nearly everyone takes it for granted without knowing where the idea came from—shows how such ideas are tied up in musical behaviors that are passed down over time.

Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical eras (ca. 1400-1800)

Musicians in these periods tended to be born rather than made. That’s not a knock against how hard they worked, just a pithy way of saying that in music, as in most other trades (e.g, blacksmiths, carpenters, farmers), fathers passed their skills directly to their children by teaching them to follow in their footsteps, and most education took place in the home. Most of the “big name” composers we’ll come across in class learned their craft or at least began their studies with their fathers at an early age (around 3 or 4 years old), who were themselves musicians who had learned from their fathers, who had learned from their fathers…

Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Ludwig van Beethoven (more on Beethoven in an upcoming online discussion!) all came from families of musicians and began their studies at an early age with their fathers. They heard excellent music making happening right in front of them from their infancy and reinforced what they saw with ongoing lessons in playing (usually keyboard, violin, and singing) and composition.

An important distinction of the post-Medieval era is that knowledge was more widely available beyond the monastery or the nunnery. Major universities were established in the Medieval period that grew in the Renaissance and beyond (Bologna, 1088; Oxford, 1096; Salamanca, 1134; Cambridge, 1209; Padua, 1222; Naples, 1224; Sorbonne, 1150). The invention of a printing press with movable type by Johannes Gutenberg in the mid-15th century facilitated the spread of knowledge, too. Both of these developments help support the general cultural trend towards making education fashionable—because book learning had been so rare previously, it was a mark of refinement, wealth, and quality at this point in time to be well-educated, and people who could afford to do so sought out education and ways to demonstrate their erudition.

On the musical side, there was a flowering of new treatises (rather than just copying ancient ones) written and published about music: its history, music theory, how to make music socially, how to play various instruments, and how to compose. Here’s a small but representative sample, with links to original texts wherever possible:

- Baldassare di Castiglione, Il libro del cortegiano (Book of the Courtesan, 1528)

- Antonfrancesco Doni, Dialogo della musica (Dialogue on music, 1544)

- Pontus de Tyard, Solitaire premier ou prose des Muses & de la fureur poétique (First Solitaire or Prose on the Muses and Poetic Furor, 1552)

- Gioseffo Zarlino, Istitutioni harmoniche (Harmonic Institutions, 1558)

- Henry Peacham, “The Compleat Gentleman” (1622)

- Johann Joseph Fux, Gradus ad parnassum (1725)

- Johann Mattheson, Der vollkommene Capellmeister (The Perfect Music Director, 1739)

- Johann Joachim Quantz, Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (Essay on Playing the Flute, 1752)

- Joseph Riepel, “Fundamentals of Musical Composition” (1752)

- Carl Philip Emmanuel Bach, Versuch über die wahre Art, das Clavier zu spielen (Essay on the Proper Manner of Playing A Keyboard Instrument, 1753)

- Leopold Mozart, Versuch einer gründlichen Violinschule (A Treatise on the Fundamental Principles of Violin Playing, 1756)

- Georg Sulzer, Allgemeine Theorie der schönen Künste (General Theory of the Fine Arts, 1771-74)

- Johann Philipp Kirnberger, “The Art of Strict Musical Composition,” (1776)

- Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Allgemeine Geschichte der Musik (A General History of Music, 1788-1801)

- Heinrich Christoph Koch, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Composition (Introductory Essay on Composition, 1782-93)

Music literacy—the ability to read music that is notated on a page—is central to the way classical music is taught from the Baroque era onwards. Musical notation allows musicians to share music with people who aren’t physically in front of them and to learn much more music than a single person can reasonably memorize in one lifetime. Here’s a brief video introduction to music notation:

Finally, another important method for learning music emerged in the Baroque era: conservatories. A conservatorio (for boys) or an ospedale (for girls) in Italy was an orphanage.

A conservatory’s main task was to train parent-less children in music. This may seem odd: Why teach an orphan to play violin when they don’t even have a home? But let’s take everything we’ve learned so far about the history of music into account: (1) There’s a long-standing assumption that music is crucial to making a complete human being (from the Ancient Greeks); and (2) People who have musical training are considered cultured and valuable (because it was was rare to have access to it). Given that, it’s pretty clear why people caring for orphans—children who have nothing, no money, no land, no dowry—would give those children some cultural capital in the form of musical training. Even a child with no family has something to offer if they can make music. For boys, that meant the potential to make a living—the fact that they didn’t have a father to teach them was no longer an impediment to success. For girls, this typically meant that they became marriageable—the fact that they could make beautiful music made them more attractive to a potential (rich) husband (more on this idea in another upcoming online discussion!).

What kind of music did these orphans play? Probably something like this this, which is a piece you’ve probably heard in commercials, hold music on the telephone, or other media:

It’s by a Baroque composer, Antonio Vivaldi (1683-1741), who taught violin at the Ospedale della Pietà in Venice, Italy (pictured above). He wrote hundreds of concertos like this (with a soloist standing in front of an ensemble that accompanies them). At the orphanage, likely Vivaldi himself would have played the solo part, with his students accompanying him. If he had an exceptionally talented student, she would have played the solo.

Romantic Era (basically the 19th century)

The goal of most music education in the Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical eras was to turn the student into a competent professional musician: someone whose entire career revolves around music making in many ways (composing, performing, playing multiple instruments, teaching, and writing about music). The most important shift that happens in the Romantic era is an increase in amateur music making: doing it for fun rather than for money.

(Hey, this is one of those cycle things again! Music has always been made for fun, but the people doing that in the Renaissance, Baroque, and Classical eras were members of the nobility and aristocracy. In the 19th century, people who didn’t have titles like “King” or “Duke” are able to make music, too—what had been elite becomes common.)

A common pastime in 19th-century Europe was making music at home—singing songs or playing chamber music with the family to pass the evening, playing for guests to entertain them (and to show off!), and keeping female children busy. People would learn to play an instrument and read music by hiring a professional musician to be their private teacher.

University-level music appreciation classes—just like this class you’re taking right now—first appeared in the 19th century in Germany. This tells us some important things about the cultural landscape of the 19th century:

- People still thought that music was really important (those Greek ideals aren’t going away!),

- But not everyone felt like they understood music as well as they should (and they wanted to remedy that situation by studying), and

- Musical styles changed, and the kind of music being composed at the time was harder to understand just from hearing it once without some amount of training or background information.

Education of professional musicians was different; it didn’t take place in the home or in a university. People who showed particular musical talent at an early age in the 19th century didn’t study music with their fathers—middle class parents in the Romantic era were more likely to be teachers, government officials, or lawyers than musicians. Instead, they sent their children to the local (or regional) conservatory.

Wait a minute! Weren’t conservatories just orphanages with musical training? Yes, originally (see above), but once people realized how effective musical training could be if you kept kids captive and immersed in music education, they started choosing to have conservatories take their children and train them professionally. The major music conservatories in Europe that are still active today were established in the early 19th century:

- Paris, 1795

- Bologna, 1804

- Milan, 1807

- Florence, 1811

- Prague, 1811

- Warsaw, 1821

- Vienna, 1821

- Royal Academy of Music in London, 1822

- The Hague, 1826

- Liège, 1827

Children would typically enter the conservatory between the ages of 5 and 15 and study music there exclusively—no literature, no math, no science—and intensively for 10-15 years. They’d become proficient in all the skills necessary to make music at the highest level: composition, counterpoint, performance, sight singing, and conducting. Many of the “big name” composers you’ll come across in the 19th and 20th centuries were conservatory-trained: Hector Berlioz, Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler, Maurice Ravel, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

But what about the US? Even though the United States declared independence from Great Britain in 1776, American culture still imitated European culture. This included the assumption that having musical knowledge was crucial for a person to be fully educated and worldly. The US didn’t have the same long-standing music education tradition that Europe did, and the major US conservatories and music schools were established quite a bit later than their European counterparts:

- The Peabody Institute at Johns Hopkins University, 1857

- Oberlin Conservatory of Music, 1865

- New England Conservatory, 1867

- Boston Conservatory, 1867

- Yale School of Music, 1894

- The Juilliard School, 1905

- San Francisco Conservatory of Music, 1917

- Manhattan School of Music, 1917

- Cleveland Institute of Music, 1920

- Eastman School of Music, 1921

- The Curtis Institute of Music, 1924

- The Colburn School, 1950

Without the same quality of musical training available, American orchestras and opera companies often weren’t as proficient as their European counterparts, and audiences weren’t as culturally savvy. Some American musicians experienced a fair amount of culture-envy or cultural inadequacy when they compared music making in America to the institutions of Europe.

One such musician, William Henry Fry (1813-64), staged a series of lengthy, dense public lectures in New York City in 1853 in a feverish attempt to bring the uncultured (or so he thought) American public up to speed with the European standard-makers. Notice that his lectures precede the establishment of any conservatories in the US—other people clearly felt the same pressure and put their efforts into institutional education.

The 20th century

The 19th-century trend of home music making (by amateurs for fun) was widespread—to the point that most middle-class families had a piano in their living room and at least one family member could play it reasonably well—until the Great Depression (1929-39). In the 20th century we again run up against another one of those social cycles: classical music making had become so common, and seemed so associated with “old people” (like parents and grandparents), that it stopped being fashionable. What was fashionable was popular music—jazz, rock, disco, hip-hop, or pop, depending on the decade in question and the audience at hand.

On top of that, the classical music made by those conservatory-trained professional musicians (who immersed themselves in all the techniques, skills, and history of music from an early age) was generally becoming even less accessible to the average listener. As an example of music from a conservatory-trained musician that is difficult for many new listeners, here’s Pierre Boulez’s Structures I (1952) and II (1962):

All of this means that the way music is learned in the 20th century is a more extreme version of trends that had already taken root in previous eras:

- Professional classical musicians were trained intensively, often from an early age, in a style of music that was becoming less and less popular;

- People who could afford it studied music privately in their homes (because they were continuing that Ancient Greek assumption that there’s value in music study!);

- Hands-on music making generally became less and less prevalent (consider that even garage bands, with self-taught teenagers playing guitars, drums, and bass, are significantly less popular now than they were 20 years ago—just a single generation); and

- The majority of the public only listened to music rather than playing it themselves, and increasingly they only listened to music that was recorded rather than played live. An oversimplified—and contentious!—description of the way music is learned today would suggest that there is a class of people who are trained to do the music making for everyone else.

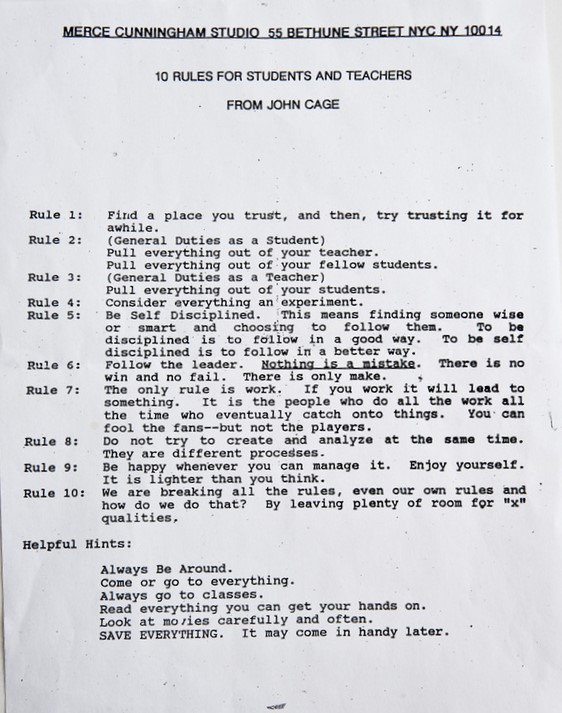

There are exceptions to all historical trends, and in class we’ve already touched upon another approach to music education from the 20th century. The poster below hung in the New York City dance studio of choreographer Merce Cunningham in the 1960s consisting of rules for teachers and students, compiled by educator Sister Corita Kent in 1967-68 and partly inspired by composer John Cage. These rules (although the word “rules” here is used ironically, since the ideas they contain are so broad as to defy the formula of typical rules that must be followed) are an effort in one corner of the art world to buck against the rigidity of the conservatory tradition and the notion of top-down learning (i.e., from professional veterans to their disciples). Cage and his partner Cunningham used these rules as a way to create a learning environment in which they and their students were encouraged to grow, explore and create freely:

Final thoughts

The question of “How is music learned?” is simplistic but not simple—the answer depends on when in history we’re talking about and who we’re talking about. The common thread in all of these music education methods is that effective learning involves meaningful and constant exposure to people who already make music at a high level, accompanied by rigorous, systematic training in many aspects of music making (e.g., multiple instruments, composition, performance). This should remind you of our last online discussion—even though historical music professionals didn’t know the neuroscience of training one’s brain, through thousands of years of passing music down people developed methods that reinforce neural pathways!

-Dr. J.

Some questions to get the conversation going

Because this is our first substantial online discussion of the semester, I’m providing a set of questions just to get the conversation started. As we proceed with these discussions, I’ll no longer add these guiding questions and trust that you have developed the critical reading skills to launch the conversation successfully on your own.

It’s most effective in an online forum like this to pick one idea at a time to respond to in a single comment, rather than combining several different ideas into one comment. And, these are just a way to get started—the best online discussions branch out into surprising new topics!

- What would be your preferred way to study music of all the methods described?

- What would happen if you adopted the Kent/Cage/Cunningham rules in your own life?

- What kinds of music making/learning does this survey omit or leave out? Why do you think they’re not included here?

- Why might knowing the history of how a subject has been taught be helpful?

- How are your own educational experiences similar or dissimilar to the ways in which music has been taught?

Good day everyone. First off, I found this interestingly – an interesting read. Initially glancing at this, I thought of what Dr. Jones stated at the beginning of the discussion text post that we tend to, “skim past others’ comments if they’re more than a couple lines long”. I thought about doing that with this post honestly, but then as I read into it – I actually wanted to continue reading because although it was a lot of information the way Dr. Jones formatted it, it was easily understood. Now… here is my real post.

I come from a Caribbean background, I was born in Guyana and having Caribbean/West Indian parents they have always stressed the importance of education. When my mother and father talked about education, they always spoke about making sure you can “read and write” and “do math”. I assume these were the only, and main subjects back home, because this is all they have ever really stressed to me. They never ever told me about learning about music, or art – but I believe that is the “old school” mentality that they have. I found it interesting that even in Ancient Greece and Medieval period that music was considered an important subject as it being part of the Quadrivium. I never really thought about music as being something teachable – I always thought of music as learning how to play an instrument and make sounds because that is what I’ve learned through elementary, middle and high school. I didn’t realize until reading this that music is actually something that has history and was considered a subject of knowledge as well encompassing what is known as music literacy. What touched me in this reading was the passage under the Baroque era, which elaborated upon the idea that orphans in conservatories who basically had nothing were given the opportunity to be trained in music. Music basically was that important that it is what gave these children a future. The males with music training would have the potential to make a life and the females with music training made them marriageable. I found this to be crazy, but also understandable because it shows the importance of music and how those who had musical training were considered cultured and valuable. I never really had a conversation with my parents and their educational experience concerning music…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Shanaiya!

SAMEE my mom would only give importance on the subjects english and math. Literally all they would say is those are the most important subjects. I remember I got like an award for music when i was little and my mom was disappointed because all the other kids got like a math award like lol ok mom crush my dreams. but anyways its great to know that music now is just a more extreme version of trends from back then. It’s kinda crazy to think what we think is “old people” music was trendy lol like imagine Beethoven on the top 100 now and you just see everyone in there cars bumping to that instead of travis scott

LikeLike

I relate to this because when coming from a Caribbean background education is grounded into you. You are told you must do this and do that in order to succeed. I was never taught the importance of broadening my education to different subjects than learning my “math and readings”.

LikeLike

Good afternoon everyone. The ways of learning how to read music is super interesting, the way that the notes are composed and how one means one beat, two beats and so on. what do you guys think?.

aside from that one of the musical periods that caught my attention was the romantic period, everyone in this period was playing music and learning because they wanted to not just because they a title in their name. Music was played for fun rather than money. What musical period was your favorite??

LikeLiked by 1 person

My musical period is the modern period. I wouldn’t say it was played just for money because it does. But the songs i love talks to me and the situation that is going on in the generations

LikeLike

Hey Manzanob I agree with you, my favorite musical period was the romantic one, I think is interesting how people just wanted to learn how to play an instrument and about music in general just for fun and no for money, Kind of difficult to find that in today’s society but I’m sure there is always the exception to the rule.

LikeLike

Hey Paula. I totally agree with you that it’s difficult to find people today in our society that are genuinely interested in music or playing an instrument and not interested in any possible money that could be a result. Anyone know someone who just loves to play or make music because the truly love music?

LikeLike

I think during all eras people played music because they wanted to or had a passion for it. But money was still a concern in historical times as it is now, and people who couldn’t afford to play music simply didn’t play music back then.

LikeLike

I’d say my favorite period would be modern music, just because of the diversity of genres there are as the world becomes more interconnected, giving us more access to a broader world of music. I also think that people who study music now are more passionate about it than previous generations, because in the past a lot of people studied music as a way out of poverty, like those orphans in the conservatories.

LikeLike

Manzanob I agree with you that learning how to read music is very interesting because it’s like learning a new language. My favorite period was the romantic period as well and I agree that Music was played for fun rather than money. That perhaps people before put more feelings to lyrics than now. What do you guys think?

LikeLike

Good evening guys, Id definitely prefer to study and practice in a hands on way , it allows u to develop your own style better and get the hang of what suits you and what doesn’t. Learning through hands on/ self taught way pushes you to do better without it feeling like work. But what do you guys think?

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is straight facts I am taking another music class where I get to play the piano and it is really interesting learning how to play. Learning hands on is definitely and easy way to learn music and how to create all types of music. You can basically do anything with music, plus there are so many different types of music combinations which makes learning about music fascinating because you never know what you can create. I have a piano at the crib so I practice by myself and I just try and play songs on the piano off memory. Not gonna lie doing that is mad hard, I be getting hella frustrated when I am playing a song and I mess up halfway through.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Michelle, I agree with you. It’s better to do thing hands on because you tend to learn better especially Visually as well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi everyone,

I like history so I enjoyed reading how music was taught. The way music as taught has change dramatically since is more accessible now than back then. I took a music class when I was a teenager and I remember that reading music was difficult therefore once I learned how to read a bit music I was so proud of reading and playing at the same time. That how I know music develops such a amazing skill at multitask and stimulates our brain in a higher level. My parents wanted me to learn how to play an instrument by saying that back in the 1800’s music was mandatory and important as any other class.. and I knew that but reading this reinforce the knowledge that music it was a mandatory and there is a reason for it. However, I believe that the 20th century perception of music is very different from before. Popular music today is not as elaborate as before, but also there is more variety and acceptation to all kinds of music genders which makes it more enjoyable a accessible to everyone around.

What you guys think?

LikeLike

Hey guys! I think the way that music was taught during the Romantic era, where the student was immersed in an environment of musical education is really interesting. It speaks to the importance of music during that period and the prestige that came along with understanding how to read and compose music along with playing an instrument. Along with Manzanob, I also agree that although there was a certain esteem that was associated with musicians, it was refreshing that people were playing music for entertainment rather than solely for money. However, isn’t it better to have a job that you enjoy rather than going to work and hating it every day?

LikeLiked by 1 person

hi everyone ! My preference of learning music would be to listen. Although some studies say that listening to music while you study isn’t good, for many people it is vital. It calms them down, which can lead to productive studying. It stated that musicians such as Johann Sebastian Bach “ They heard excellent music making happening right in front of them from their infancy and reinforced what they saw with ongoing lessons in playing” We learn the history of how a subject has been taught so that we can understand the past of the subject, the history behind why it is how it is now. Education evolves everyday and while we are still learning the present the past of anything is how we will better the future.

LikeLike

Hi guys I agree with the others as I can also relate to coming from a Caribbean home Parents will push you at all costs to ensure that education is your first priority . My specific preference to this would be an hands on approach because I feel as if that is the best way to learn something rather than to just see it when you actually do it it’s more of a chance that it will

Stick in your head rather than just seeing it or having it explained to you . I feel as if people who play instruments do have a genuine love for music so it would be a music first then money type of thing but at the same time some people are put in tough predicaments and I don’t see a problem in doing what you love to bring yourself an stable income . I believe a musician playing music all day and getting payed for it is definitely better than a person who has to wake up and do a 9-5 that they wouldn’t enjoy as much because it’s not something that a person wants to do but it has to be done

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree, people who have a genuine love for music can definitely make money on that,, rather than suffering every day at a job they don’t enjoy, even if they don’t make as much money, they’re actually enjoying themselves and doing something they have a passion for.

LikeLike

SONNNNNNNN it’s really MIDNIGHT smhhhhhh what am I doingggggg I really have to start doing these earlier LMAOOOOOO but anyway let me tell you how I feel about this article real quick, I found the part about the conservatories interesting. I was wondering if parents would visit children they sent to the conservatories, they low key just don’t want their children in the house smh. Must have been an interesting experience for the kids, but I guess what they get out of the experience will better their knowledge and make them better musicians. Naa I just went back in the article and just peeped that the kids are exclusively taught everything dealing with music so NO literature, math, and science. Naaaaaaa they were buggggiiinnnn for real back then. Those kids gonna come out smart and dumb at the same time, gonna be singing and playing their instruments like crazy but then when its time to buy something they gonna be like (9+10=21) SMH naa bro those conservatories were on CRACK at least teach them some math. What would you do if you were sent to a conservatory, what emotions would you experience and how would you act? Lmaooooo I’m listening to A BOOGIE right now so I’m in my BAGGG NOW IN MY BAG NOW HUHHHHH, LOL but he just dropped a new album Its called (ARTIST 2.0) go give it a LISTEN. My favorite song on the album is called RIGHT BACK and IM out on this one DEUCES.

LikeLike

Hi everyone! I also do prefer to practice and learn in a ‘hands on way’ like some of my fellow classmates. I think it allows you to work at your own pace without feeling pressured and it may also allow you to discover new things about yourself. Likewise with music, I think its best learned in a way that’s suitable to you hence, I prefer listening to music rather than reading the lyrics/notes and it may be vice versa with others. Thus, music can be taught in different yet interesting ways and I think they’re all fun.

LikeLike

What would be your preferred way to study music of all the methods described? A way to study music is listening to it, playing with it as I go. For other people it is different though. You can have a deeper understanding about music depending on what music you listen to. Why might knowing the history of how a subject has been taught be helpful? Knowing the history of how something was taught can be helpful because you can better understand what’s going on .

LikeLike

Hey everybody I think my way to study music is listening to the words line by line I like to think when someone is singing or rapping act like there talking to you and hear what there saying. I do like the modern music era. I do agree with wakanda about the singer A boogie with his iconic line “In my Bag now “but that’s his catch phrase and that’s what all his fans say when they think of A boogie that he’s in his bag meaning that your in your own world nobody else but you. Music can be taught in numerous ways I think learning the history the background would be a nice way to learn about it more.

LikeLike

My preferred way of studying music is through hands on activities or through visuals. This helps you by making you able to see whites going on and making it a clearer way to understand the material. Using visuals help me to stay engaged in what I am doing and understand better what I am learning. Just reading from the notebook doesn’t help me understand the material since I’m just reading.

LikeLike

I prefer listening to music directly. It doesn’t matter if I have to listen to the same piece more than once. As long as there’s at least some variety in the music, it’s interesting to listen to. Hands-on activities and visuals don’t work for me as well as listening, since music in the end is all about sound.

LikeLike

hey guys, I think one thing that I really found interesting or stood out to me was how hands-on music became less important as time went on which is pretty evident today considering how people use a variety of electronics and all different types of things to create music now but me personally I prefer interacting with music in a hands-on time of way and getting creative to see what I can come up with and also I enjoy listening to live bands only because everyone is different and everyone hears music differently and listening to live music just gives it a more real feeling if anyone understands what I’m trying to say lol. I think hand on is the most genuine interactive way to get in touch with your creative side. another thing that stood out to me was how people would rather listen to music instead of being the ones to play it, do you guys agree with that or do you think this generation has changed that standard and have been more interested in creating music, whether to share or just keep to themselves?

LikeLike

Knowing the history of a subject being taught gives you a rough idea of how the subject came to be, or why it began as a subject that can be studied in the first place. For music, knowing history allows us to appreciate styles of music perhaps we’re not accustomed to, given how different popular music is compared to say, classical music. The history of music is filled with all kinds of different styles of music, so knowing a bit of history helps.

LikeLike

I agree with you on this because an element that’s part of music is culture. Without culture and the knowledge that comes along with different types of music and unique styles, how would we ever know how to proceed in performing with certain types of instruments. Behind every instrument there was history made behind that object, that it is why in my opinion learning about music in general is important because it allows the public to give respects to the artist and the background.

LikeLike

Wassup, this was a cool read. I prefer learning music in more of a auditory way, since I’m surrounded by and grew up around rap culture. You listen to people rap, and you also rap in freestyle cyphers. Yeah, hands on music is becoming less used in the industry these days as young people just want a dope beat with mumble rap on it. It’s just my opinion, not facts. Just like beauty is in the eye of the beholder, music is in the ear of the beholder. Listen to what you what you prefer and play what you like!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Classmates,

Knowing the history of how a subject has been taught is very helpful. It allows us to understand the subject( music) in retrospect and today’s world. Music’s history can also give us insight into why our culture does certain things. Up until the modern era we were following the European culture; I wonder how that would be in today’s world.

I believe learning music’s history is like having a rough draft and you’re adding your final touches. Learn, master it, and make it into your own style.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey guys! So what really caught my attention were the Kent/Cage/Cunningham rules. These rules resonated with me because they could be applied to everyday life. As I read them, I was wondering where in my everyday life I could put into play. How could they be used in work? In school? In almost everything. The ones that stood out the most were rules 7 and 9. Work; whatever the work is, do it and you will gain the necessary tools you will need to do the work. And don’t take things to seriously and just have fun with it!

What do you guys think?

LikeLike

This topic about musical education really triggered me because I somehow can relate to it deeply. My family in from a Chinese background in Fuzhou, China. That’s the part of China where music isn’t really significant in the culture. It is a place where people only thought about money, money, money, good education, get a good job, live life happy, and again, money. As I bring up the get a good job part is that most Fuzhounese parents expects their kids to get jobs in a company or office environment, a place where you can work comfortably and get paid more than “typical” restaurant jobs. So that’s true for most Fuzhounese families. Hence, no one in my family was a musician. I did not grow up with any musical background. And to be honest, when I was a kid in elementary school, I took music for granted. I didn’t like it very much. I thought it was the most useless subject because I thought I was not going to ever engage in music in my future. I didn’t really pay much attention in class. At the time, I even thought playing the piano was impossible for me because every black and white keys looked the same. Things changed dramatically for me as I entered middle school. I started to become an audiophile to the point where I would have a set of earbuds every single day when I go to school. I became addicted to music, and started loving it. I would feel very awkward if I didn’t bring earbuds on me to school, and I still do to this day. At the time, I knew that I wanted to become a composer, lyricist, and singer of my own songs in the future. That thought never died out til this day. During the beginning of 6th grade, I wanted to learn singing. What I did back then was watching Youtube vocal tutorials because I couldn’t get private vocal lessons. It kind of worked a bit. I guess? But I do know that I sound horrendous back then. I lacked the knowledge of musical notation. I thought I was on pitch when I really wasn’t. It was that bad. As I entered 8th grade, I took a music class where the teacher taught to play various instruments and music notation. That’s where I learned to play the basics of a piano and guitar, and gain some musical notation knowledge. I felt enlightened because what I thought was impossible for me to do became possible. I was surprised that I exactly understood the basics of the piano, guitar, and music notation. Learning music notation really sparked my mind into thinking how important it is for a musician. It is like the center piece of all music. You must know music notation to a certain degree to play any instrument (including vocal) and compose music. Knowing music notation made me love music even more because I started to really understand it in depth. Throughout high school, I was desperate for music classes since the seats in music electives were very limited. During high school, I started taking chorus and piano to improve my singing and piano. And now here I am in college as a music production major. Thankfully my parents aren’t against my decision for my future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry for whoever’s reading it because there is a typo in the beginning that is too late to be corrected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One interesting trend that I’ve noticed in the history of the teaching of music is how as it became more and more accessible to the masses, its appeal of being taught and being an essential part of a person’s education has slowly diminished. In medieval times and Ancient Greece, music was taught with the same importance as math and science. As time passed, music went from being taught in monasteries and special conservatories to major universities and music institutions. With this wide accessibility, by the 19th century and up until the early 20th century, music was being taught at home and was made for fun. The more fun it was becoming, the less importance the classical elements of music were given, and younger people strayed away from traditional types of music, common among older generations, and more towards popular genres such as rock, jazz, and disco.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello everyone, knowing the history of the subject we are learning might be helpful to us because we are getting an idea of what to expect. Also, we start to appreciate the subject and everything that has be done in the subject. i would say that the method for me that will be easier for me to learn will be hands-on because you are getting the experience and also you can create a way that will benefit you

What are methods that help you learn?

LikeLike