This final of our instructor-led online discussions for Mu 101 (Fall 2019). Refer to the handout you received the first day of class (click on this highlighted text to go to that page our class website) which describes the amount and kinds of contributions you’re expected to make to these online discussions — they’re all the same parameters of good conversation that happens offline, too!

The approximate reading time of this post is 12 minutes, not counting any audio media.

https://www.gettyimages.com/collaboration/boards/QwTWlw3wLk6Pmktr8vLmRA

We’ll begin this online discussion as you might expect: listening to a piece of music inspired by violence. The Croatian town of Vukovar had been decimated during the Yugoslavian Civil War in 1991 (pictured above in the slideshow of Getty Images). In 1999, American composer Laura Kaminsky visited Vukovar on a peacekeeping mission, unprepared for the level of destruction she saw 8 years after the war, and the devastation weighed on her so heavily that the next time she sat at a piano, the beginnings of this piece emerged. She dedicated her Vukovar Trio to the victims of ethnic cleansing. It’s performed in one movement of connected but contrasting sections, each of which has a vivid subtitle in the score: A Sky Torn Asunder; The Shattering of Glass; Lost Souls; Revenge/Retreat; Death Chorale; River of Blood and Ice; Ghost Chorale; Dance of Devastation

The online music journal New Music Box interviewed Kaminsky and asked her about this work in 2013:

When I was living in Poland and running the European Mozart Academy, we took small groups of chamber musicians throughout central Europe to give concerts. One of the concerts arranged was to go into Vukovar under Human Rights Watch protection and give the first live concert since the official end of the war at the fairly devastated Serb Cultural Center. Going into that devastated war-torn city was really eye-opening and very humbling for all of us. We were really quite taken aback by seeing the destruction. This was three years since the end of the war; people still had no electricity and there were food shortages. It was grim; you could tell that this was not a good place. When I say Vukovar, like I’m talking to you now, to this day I’m seeing this picture in my head. Somehow I had to deal with that picture. I knew I needed to write a piece, and I wanted to write a piano trio, partially because I was living in Eastern Europe and that sound world was so much what I was breathing and hearing every day. I felt like I wanted to write an homage to Shostakovich and his great trio which is such an iconic piece. Then I thought, his Eighth String Quartet is dedicated to the victims of fascism and war; I would dedicate my piece to the victims of ethnic cleansing. I hate to say this, but most Americans don’t read the headlines. It’s history already. I wanted to keep [in people’s minds] the fact that genocide is alive today, so I gave it that title. But I did think about just calling it Piano Trio.

Frank J. Oteri, interview: “Laura Kaminsky: Every Place Has a Story” (New Music Box, October 2013)

The relationship between music and violence isn’t always so straightforward—it’s not just about how violence inspires musical sounds. Music has the power to convey messages—through its words, because of the context where it’s played, because of who’s playing it, and because of our associations with similar musical sounds. (The study of how music is able to convey messages, imply ideas, or communicate subtleties to nuanced listeners is called semiotics.) This week, we’re thinking about how violence is enhanced by music, inspires music, and allows music to take on new meaning. The focus will be on 20th– and 21st-century wars (World War II, Vietnam, Iraq/Afghanistan post-September 11th), and we’ll think about four different ways that music intersects with violence: nationalism, the human toll of war, music as protest, and music as war.

I. Nationalism and patriotism: Music to unite the people

Nationalism (celebrating one’s nation) was a common political and musical theme in the 19th century. Nationalistic music was composed and celebrated all across Europe as the nations that populate the map as we now know it were being formed: Italians rallying around the king of a newly unified Italy (Vittore Emanuele II) and using the operas of Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) to do so, Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904) composing music that celebrated his homeland of Bohemia (now the Czech Republic), Edvard Grieg (1843-1907) doing the same in Norway, and Jean Sibelius (1865-1957) doing the same in Finland.

The same thing happened in the United States, particularly in the form of local town bands that played marches in parades after the Civil War. John Philipp Sousa (1854-1932), for example, made his career composing 137 marches and serving as Director of the US Marine Band and later his own professional band, the Sousa Band. One of his marches, The Stars and Stripes Forever (1896), was named the national march of the US in 1987.

Nationalistic music is often simplistic, with clear, obvious, and steady rhythms—things that can get a crowd of people clapping along, making them musically united as long as the music sounds. In music of this style, melodies are often clearly differentiated in the texture and are characteristically rousing, encouraging, or uplifting. The form of a Sousa march always concludes with a polyphonic texture [3:58 in the above video], allowing the composer to add depth and nuance of the idea he’s celebrating (i.e., America) by simultaneously layering different melodies on top of each other. On top of that, marches like these were played as part of larger patriotic displays, with flags waving, veterans marching, and stirring speeches—all things that resonated with and amplified the music’s message.

The last piece of nationalistic music I’ll leave you with is Toby Keith’s Courtesy of the Red, White, and Blue (2002), a song written during peak post-9/11 fervor that captures the ideologies of American protectionism, American exceptionalism, and anti-foreigner sentiment. It encapsulates everything we can expect from propaganda-music: it’s catchy and simple, it leaves no room for subtlety or nuance (“We’ll stick a boot in your ass / It’s the American way”), and it spreads a particular idea among a group for political purposes. The imagery of the video (gently billowing American flags, cowboy hats and cut-off sleeves of the southern working class, US soldiers in battle fatigues, and guns) reinforces the propagandist message.

These are all examples of propaganda: music that conveys a political message, and this makes sense in wartime. In a time of crisis and stress on the population, anything that leaders or the military can do to build resolve and support for the long road ahead is a smart strategy. Music’s effectiveness as propaganda (i.e., manipulation towards political ends—the composer Christian Wolff (b. 1934) goes so far as to say that “All music is propaganda music.”) is based on the power of music to incite particular feelings and thoughts in your mind, especially when coupled with context, power, or a threat.

II. The human toll of war

The Crusades

Europeans have been fighting over the Middle East and fighting the people who live there for centuries. The Crusades were a series of wars fought by Europeans on behalf of the Catholic Church and the Western world for nearly two centuries (1095-1291).

These wars resulted in thousands of deaths, great tales and fables of bravery, the exchange of goods and ideas from East to West and vice-versa, and, of course, the capturing of prisoners. One such prisoner was the King of England, Richard I, aka Richard the Lionheart (1157-99). He was captured while returning home and held for ransom by Duke Leopold of Austria (1192-94). His traveling and captivity in the Crusades are part of the story of Robin Hood—his brother Prince John held the throne while Richard was away, overtaxing the people of England and generally being an inept ruler (with the help of the Sheriff of Nottingham).

While in captivity, Richard I wrote a song about his sorrow, resolve, and homesickness, “Ja nuls homs pris” (No man who is imprisoned).

No man in prison can tell his tale true

Lest he himself has known what I’ve been through

In writing song he may comfort renew

I’ve many friends but their gifts are few

They’ll bring dishonor for my ransom’s due

These two long winters pastMy noble barons and men surely knew

England and Normandy, Gascon and Poitou

Ne’re would I forsake or be untrue

To any friend; noble, commoner too.

I do not mean to reproach what they do,

Yet I remain held fast

World War II

Olivier Messaien (1908-92) was a French composer trained at the Paris Conservatoire. When World War II broke out, he served in a medical unit in the French army but was captured in 1940 and sent to prisoner-of-war camp in Poland called Stalag VIII-A. One of his German guards recognized him and provided Messaien with everything he needed to continue to compose: sheet music, pencils, a piano, and instruments that could be played by the other professional musicians in the camp (clarinet, violin, and cello).

Messaien wrote a work that he called Quatour pour la fin du temps (Quartet for the End of Time)—an ominous and heavy title that reflects the feeling of the entire world coming to an end as much of France was destroyed by the German occupation, as winter settled on the camp, and as the prisoners couldn’t find out whether their families were still alive. Two important factors shape the sound of this piece: (1) the instrumentation, and (2) Messaien’s religious faith.

There were three other professional musicians imprisoned in the camp, a clarinetist, a violinist, and a cellist. The guards were able to procure instruments for all of them that were, by all accounts, terrible but playable. Messiaen’s quartet is special partly because no composer had ever previously combined these instruments—this piece is driven by the limited resources available to the composer.

In addition, Messaien took great comfort in his faith—he was Catholic—and his inspiration for the piece came from the Book of Revelation in the Bible that he experienced in a dream:

“And I saw another mighty angel come down from heaven, clothed with a cloud: and a rainbow was upon his head, and his face was as it were the sun, and his feet as pillars of fire…and he set his right foot upon the sea, and his left foot on the earth… And the angel which I saw stand upon the sea and upon the earth lifted up his hand to heaven, and sware by him that liveth for ever and ever… that there should be time no longer: But in the days of the voice of the seventh angel, when he shall begin to sound, the mystery of God should be finished.”

—Revelation 10:1-7, King James Version

Messaien regarded death and destruction on Earth not as a terrible end but as a hopeful beginning, the chance to begin eternal life in heaven. Here is the end of Quatour, in which you’ll hear very long notes in the violin reaching ever higher, on top of chords, two at a time, in the piano—the violin calm and graceful no matter what the piano does underneath, and the symbolism of ascending to heaven is pretty clear. The premiere, held outdoors in the middle of winter, was attended by the guards and inmates of the camp, who were already weary of the war and held in rapt attention for the entire work. Describing the experience later, Messaien said, “Never have I been heard with as much attention and understanding.”

World War II, continued

Polish composer Krysztof Penderecki (b. 1933) composed the next work without a title or inspiration in 1960, and only after he had written it and grasped how intense, emotional, and catastrophic the piece sounded did he give it a name: Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.

A threnody is a kind of song, hymn, or ode for someone who has died; it has a wailing quality and is often performed as a memorial. Hiroshima was the site of the first atomic bomb detonation in wartime, on August 6, 1945.

III. Music as protest: Giving voice to those not in power

Music played a large role in American anti-Vietnam War protests in the 1960s, expanding protesters’ message beyond just disagreement with a specific war to a broad, public polemic against all violence. Woodstock (August 15-18, 1969) was the capstone of ongoing protests by young, often white and middle class Americans against the use of violence generally, the Vietnam War specifically, and other ideas that they associated with “the establishment” (their parents’ and grandparents’ generation who were in charge of the social, political, and governmental structures that led the country into this morass in the first place) and all things the establishment stood for: the American Dream, being uptight or “square,” capitalism, anti-drug use, monogamy and heterosexuality, and—of course—anti-rock music.

The power of Woodstock and the music by rock and folk musicians who performed there lay in uniting a large group of people (400,000 attendees plus more who sympathized but couldn’t attend), articulating a message contrary to that espoused by people in traditional positions of power, and doing so in a way that was pleasant, persuasive, and enticing for a certain group: young people liked this kind of music and were drawn to it, whereas older Americans were not.

Performers included rock bands (Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Janis Joplin, The Who, Jefferson Airplane, Joe Cocker, Crosby Stills Nash & Young), world music and fusion groups (Santana, Ravi Shankar, Sly & the Family Stone, Blood Sweat & Tears), and folk singers (Joan Baez, Arlo Guthrie).

Here’s Country Joe McDonald performing Vietnam Song which he wrote specifically for the festival:

Jimi Hendrix played the last set of the festival (approximately 130 minutes long), and his solo performance of The Star-Spangled Banner (the US national anthem) was particularly powerful because it was both an extraordinary display of his skill and creativity as a guitarist as well as a musical protest—it audibly and prominently distorted the melody and form of national anthem, and in the process re-purposed it from a bland, patriotic gesture into a personal claim: “There is room in America for me, for people like me, for my ideas, and for me to shape America into the country I want it to become.”

Coming on the heels of the Civil Rights movement (1919-68), the assassinations of Malcolm X (1965) and Martin Luther King, Jr. (1968), and in the middle of general dissatisfaction with the country, Hendrix’s performance made a powerful statement.

US football player Colin Kaepernick’s protest of the national anthem during the fall 2016 NFL season can be seen in the same context. As a racial minority in the US, Kaepernick listened to the anthem, saw the display of celebration and pride that it encompassed, and found those to be in dissonance with his experience as an American and the experience of other Americans. Rather than stand during the playing of the anthem at San Francisco 49ers games, he took a knee on the sideline, causing uproar for viewers who took his gesture to be a direct affront and insult to members of the military. The fact that his gesture could be interpreted so differently speaks to the powerful place that the anthem occupies in people’s imaginations and how strongly they associate the musical sounds with political ideas.

Kaepernick’s gesture also encouraged a broader re-examination of the Banner itself, which was written by Francis Scott Key following the Battle of Fort McHenry in Baltimore during the War of 1812. (It became the US national anthem in 1931.) The song has four verses, but we typically only sing the first in public events today. The third verse, which celebrates the deaths of slaves who were promised freedom by the British if they defected to the Royal ships in the harbor but were killed by American fusillade, makes the song problematic.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave,

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave

O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Because the national anthem is a powerful symbol of the nation it represents, a person who questions it or seems to lack complete faith in that symbol can be interpreted as disrespectful, not just of the song but of the nation itself. This conflation is an example of false logic, obviously, but also the fact that such a reaction is possible shows just how effective the song is as a piece of propaganda. Kaepernick’s career seems to be over as a result of his protest, further underscoring the weight people ascribe to the anthem as a patriotic symbol.

IV. Music as war

Armies have been using music in battle as long as there have been battles. Drums keep armies in step, trumpet fanfares signal which units should advance, and the enemy can hear music of an approaching army long before they see them—allowing fear to set in if the approaching army sounds big and powerful.

During the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars (1526-1791), Turkish armies made use of psychological warfare by having their Janissary bands perform outside the walls of a city under siege, psyching up their own troops and intimidating the citizens trapped inside. For Europeans, the Turks’ use of percussion (especially metallic percussion) and nasal-sounding wind instruments would have been frightening because of its unfamiliarity, and large, coordinated ensembles of musicians can have an intimidating effect. (Also recall that many of these percussion instruments migrated into the European orchestra and are part of its standard instrumentation today).

Music as psychological warfare continues today, and Jonathan Pieslak’s book Sound Targets: American Soldiers and Music in the Iraq War (2009) explores how American troops and interrogators typically use heavy metal and rap to pump themselves up for battle and to rattle prisoners during interrogations. I strongly recommend that you read Alex Ross’s excellent article “When Music is Violence” in The New Yorker (2016), which summarizes Pieslak’s book and other instances of music being used to inflict harm on others and shows how broadly you can approach the idea of listening to music: Ross – When Music Is Violence – The New Yorker

Final thoughts

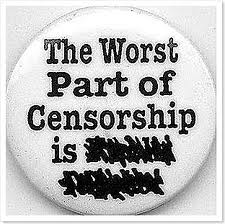

It’s difficult to talk about war without also thinking about censorship, the control of the spread of ideas. Music is a powerful means of conveying messages, and the potential flip side of this power is the rejection of that message (and the messenger/musician) in the form of boycotts, commercial failure, and censorship.

Art is a way to express ourselves at our best, or at our most profound, or ourselves in our best image. And it’s a way for us as listeners to explore, empathize with, and experience other people’s lives and perspectives. The arts and literature are among the first targets of tyranny and censorship because they open people’s eyes – to different ways of life, to different perspectives, to alternative realities. We humans are by nature inquisitive creatures, and when confronted with something new, we ask ourselves how it could exist, what has caused it to come into being. We imagine what sort of person might have come up with a piece of art, what kind of world a person who writes a certain song could live in. And if we start imagining other people and other perspectives, we might be tempted to change our own, and that is the wonderful danger of art.

Art is a way to express ourselves at our best, or at our most profound, or ourselves in our best image. And it’s a way for us as listeners to explore, empathize with, and experience other people’s lives and perspectives. The arts and literature are among the first targets of tyranny and censorship because they open people’s eyes – to different ways of life, to different perspectives, to alternative realities. We humans are by nature inquisitive creatures, and when confronted with something new, we ask ourselves how it could exist, what has caused it to come into being. We imagine what sort of person might have come up with a piece of art, what kind of world a person who writes a certain song could live in. And if we start imagining other people and other perspectives, we might be tempted to change our own, and that is the wonderful danger of art.

-Dr. J.

I believe that, before radios and other communication devices existed, armies would use various musical sounds to signal their troops on the battlefield. For example, they would use something like drums to alert to the enemies’ presence, use trumpets to order the troops to retreat, and maybe use a whistle or something to order them to attack.

But, eventually, we invented communication devices which allow us to communicate without having to use instruments or possibly give away our position to the enemy in the case of a stealth mission.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with what you are saying because communication face to face or from a distance by mail or such was the only way to hear from anybody, until radios or beepers or even cellphones where created.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Armies have been using music in battle as long as there have been battles. Drums keep armies in step, trumpet fanfares signal which units should advance, and the enemy can hear music of an approaching army long before they see them—allowing fear to set in if the approaching army sounds big and powerful.”

LikeLike

I agree with you soilders did made sound with there month. Different sounds meant different thing.

LikeLike

I think that when there was a tragic moment that happened making music was an coping way to express stress or the worries that was happening around that specific person or society.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Music and violence, is a great topic. I want to start by saying human and animal have five innate senses. In my opinion, the ability to hear is the most important out the five. Even during mythical and biblical times, we have learned that people were afraid of loud sounds. The thunders of Gods, the loud voices of troupes marching outside the wall of a city, the distant trumpets of an approaching army and sum of propellers from a convoy of enemy planes. The unknown is now evident. The reality sets in and danger is eminent.

Music and sounds have always been used to strike fear or to send a message of rebellion. We have gangster raps, where the artist’s music portrays a so called “I don’t care attitude” projecting fear in whomever want to come test his or her crew. There is a psychological connection between certain sounds, lyric and drawings. Just like 20th century painting as impressionism fallowed music and art has expressionisms, music can send a powerful message. For example, “Beat it” by Michael Jackson. What do you guys think the message is?

Finally, whether to strike fear or to convey discontent feelings, music is or will remain a useful tool to connect with others.

LikeLike

I’m curious to know more about the biblical times and a fear of sounds. Can you tell me more?

LikeLiked by 1 person

We sometimes tend to fear scary/unfamiliar sounds. Like if you go in a forest and you hear a big roaring sound, or a hissing sound you would instinctively avoid the source of that sound since you would assume that the sound was coming from a bear or snake.

Animals tend to avoid scary/unfamiliar sounds too, because of this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Remember this Biblical story;

“Joshua 6:20

So when the trumpets sounded, the people shouted. When they heard the blast of the trumpet, the people gave a great shout, and the wall collapsed. The people charged into the city, each man straight ahead, and captured the city”.

This was probably very scary for the opposite Army behind the wall.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think so too

LikeLike

Interesting stuff. When I think of music and violence, I always think about hip-hop. H.H. is almost always degraded for its expressive qualities. Thank you for not doing that in this posting.

Loved the Messiaen’s quartet part. Being resourceful and being innovative is inspiring. It reminds me to do what you have to do and make it work.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What makes hip-hop violent?

LikeLike

Hip Hop was never meant to express violence. If we go back to the beginning of how hip hop was we see that it was just an expression of art. We also seen it in graffiti on the walls and even fashion and choreography with break dancing. Plant Rock by Afrika Bambaataa is the perfect example of this. Don’t get me wrong Hip Hop has had there bad moments but so has everything else.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Someone was curious about noise in biblical times , well I’m not sure if when the flood with Noah and the ark is a good example not many took it seriously but who took it serious was saved . But before the flood there was thunder n maybe people would Be scared that the lord is coming . Or when Jona and the shark . Maybe the sound of the splashes would have scared everyone that was there.

Not sure if that’s what he was saying.

LikeLike

Are music and noise the same thing?

LikeLike

Overall though music and violence rings many bells , sometimes at concerts people are trying to be in the front to see the performances and that can cause conflicts.

Currently we even have artist singing violent music to each other to get more fame

LikeLike

What exactly do you think makes a music violent?

LikeLike

Rap battles can get heated and verbally violent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True

LikeLike

it’s expression

LikeLike

moreover, these guys will get into each other’s faces and closer to each other’s ears and telling lines that are provocative and disrespectful. These day and age, rap battles are not H. H. I think it has become uncensored verbal assault. More often, these battles will lead to uncontrolled physical altercations.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Although I’m not very knowledgeable about Hip-Hop, I agree with you that many rap battles nowadays shouldn’t be classified as Hip-Hop because in my opinion many “artists” now use a music genre or style as a pretense to insult others and create unnecessary altercations that unleash more violence as there have been many instances where rap battled have shifted into actual physical fights.

LikeLike

I think what makes music violent is the lyrics. What your saying can be violent or aggressive. I don’t it necessary pertains to rap only. One good example of violent lyrics would be when Eminem wrote that song about his wife Kim : I shoulda known better when you started to act weird

We coulda— hey, where you going? Get back here!

You can’t run from me, Kim! It’s just us, nobody else

You’re only makin’ this harder on yourself!

Ha-ha, got ya! Go ahead, yell!

Here, I’ll scream with you, “Ah, somebody help!”

Don’t you get it, bitch? No one can hear you!

Now shut the fuck up and get what’s comin’ to you!

You were supposed to love me!

Now bleed, bitch, bleed! Bleed, bitch, bleed! Bleed!

I think this seems to portray a pretty violent scenario and obviously there are worse things but music can definitely be violent and some people feel like it speaks to them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I personally think the choice of words like guns, and shooting in a lyrics can promote violence because everyone interpret things differently.

LikeLike

This topic really hit a lot of feelings. In a lot of aspects we can say this was an expression of strong feelings which can lead to violence and/or artistic movements inspired by violence. If we see when we look at the example of music being played as intimidation in war I’m pretty sure some of that parts of music lead to inspire someone down the line to make music out of that piece. All in all war and fighting sucks but it also has a place in inspiring art especially if there was a lost and the only way to coop is through pieces of music!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I completely agree.

LikeLike

I agree, i also feel that there will always be a connection to music and violence no matter if it’s good or bad.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I agree because remember, if music as an art form can show or dipect expressionism; we as human being have no choice but to accept or be the recipient of whatever message lies within the actual piece. Therefore, if the artist feels angree, sad or seeks violence, we will project just that.

LikeLike

What do you mean

LikeLike

Nothing is wrong with that as long as people have limits and don’t go to kill people as a consequence.

LikeLike

Not only is music inspired by violence post-war, but so many folk songs in our culture come from songs created by soldiers at wartime. So many familiar melodies we all know come from songs that were sung during the revolutionary and civil wars. We often change the words into silly child friendly camp songs, but they’re still rooted in war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

oftentimes singing together was the only way for soldiers to keep up their morale. They used it as a coping mechanism for the violent horrors they were suffering.

LikeLike

Thank God for music it is great for those reasons.

LikeLike

I agree

LikeLike

Nationalistic music is an interesting topic. It inspires pride in a country, but often, that pride is unearned or even wrong. When you hear stories from dictatorships, former citizens will tell stories about the songs that they had to sing in school or at events. Russia, for example, made it’s citizens start their day by singing about how stalin would always take care of them and how much he loved them and they loved him. I think music can be used to gloss over violence, to make an ugly world seem beautiful, and also to justify violence by making people think that it is in the service of making a better world.

LikeLike

Definitely. Putting propaganda to a catchy tune sure drives it into people heads easier. Its the same concept as using music to teach something. Putting important facts to music makes them way easier to memorize. I still remember all my multiplication tables because of music. I can recite the entire preamble to the constitution, but only if i sing the song that goes with it in my head. Tis tactic could easily be used to condition people to believe a certain thing or think a certain way. If your constituency does not have access to proper information they are very easy to control with these methods.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This was perfectly said.

LikeLike

I never thought about wars happening and sides playing music to intimidate the allies as much as I do now until I read this. It isnakso interesting that music has also been used as propaganda throughout history, And a song can make a political view seem very convincing and will probably make you want to believe it. Seeing images and videos of soldiers saluting, the colours if the flags and Americans celebrating with a song is a powerful way to convince someone to believe in a political agenda.

LikeLike

Using music to intimidate the others was something new I learned.

LikeLike

that is right, music is a psychological weapon for certain fields.

Example: Taylor Swift created some songs as a way to insult some people

LikeLike

Me as well. But also we sort of had a idea

LikeLike

Music and violence I feel have a strong connection this can be supported by many instances in history , not necessarily thats music leads to violence but that violent events create different emotions that people express or advocate what they feel. The beetles can be a good example of the music and violence connection because during the war they used there music and a form of peace.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Or on the opposite end of the spectrum, people used other music like “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” by Patrick S Gilmore 1863, as motivation for war and patriotism.

LikeLike

What I haven’t seen anyone mention is that music is not inherently violent. If we learned anything in this class, it’s that music does not have one set meaning. The listener plays a role in music. So, for example, American patriotic music can mean different things to different people, even if it’s the same song. For some, it is about the country that grants them more freedom than any other country, but for others it can be about a country that is still using institutionalized oppression to keep them down. It can be a call to bring our troops home or a call to go to war.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great point.

LikeLike

It’s how we interpret music differently.

LikeLike

Exactly.

LikeLike

Vukovar trio was something I do not like. I think the artists learned to put meaning in their composition by learning what people like to be connected to happy music and what people don’t like to something sad and depressing.

LikeLike

“Music and Violence”, these two words has nothing in common, but the first word can give incentive to the later one. In this century, music has been, one of the many categories, shaping the lifestyle of people, and so if the music invokes violence, then destruction comes in.

Music is just a way to express someone emotions, so if violence is what they want, then they might achieved, because people can act accordingly of the music.

I have an question: is there any music that invokes a neutral emotion? that wouldn’t invoke emotions.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This topic relates to what we were talking about in class. About how slave or prisoners would sing and do their work to maintain a pace and rhythm during work. I can see it in the army when they marching and saying left right left.

LikeLike

I agree, music can be a motivation to keep ourselves going. mentally and physically. I guess that’s why people often listen to music when they work out.

LikeLike

As someone mentioned before, music isn’t inherently violent nor peaceful but it all depends on the creator and the audience; consequently, music will always generate an emotion whether it be one of harmony or one of hostility according to the individual, though, sometimes it certainly can be very much influenced by the environment surrounding that person or the content inside the piece of music such as the lyrics.

As it was mentioned in the blog, the remaining three verses of the national anthem is mostly if not always disregarded, but if every single person was to be aware of it, do you think there would be an uproar that might incite a protest or a even a revolt?

LikeLike

I totally agree. Music in itself is neither good nor evil, it’s just what it is. It is only when a person takes it and twists it to fit their narrative that it has the potential to become actually violent.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Before I read this online discussion I felt the only connection between music and violence was hip hop/ rap music because of the violent language in the lyrics in some of the songs like guns, drugs, shooting etc, that I think was promoting violence.

Reading and listening to other songs that were connected to violence make me realize a song connected to violence don’t have to actually be violent, but rather making music that relate to violence is a way some artist express the pain and hurt during a violent period in their lives and their country that connect everyone one way or the other. It’s also a way of giving people hope.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I agree with this. Sometimes the violence being expressed it just merely a form of expression without trying to take any action. I think who is affected the most are the people who can’t tell the art apart from real life. They use these songs as a push to do horrible things, which sucks.

LikeLike

I thought the same thing.

LikeLike

We all hear music differently and maybe some people get provoked by certain lyrics/songs. Take Marilyn Manson and the columbine massacre. Everyone would blame him, his influence, and his lyrics, affecting these kids enough to commit a massacre. For a while he had to cancel all his shows and appearances but when he spoke about it he that he does not promote violence, hate, suicide, and the other atrocities of which he has been accused. Rather, he promotes not being afraid to be different and to challenge societal views and norms. He repeatedly asserted that there is a difference between art and real life. Maybe some people don’t see the difference.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a huge fan of both Manson and Slipknot when I was 15 and I remember wanting Manson’s autobiography soooo badly. When my mom told me no 500 times, I managed to finesse a PDF version on the internet. He’s actually very articulate and a generally open minded person who exploits how exactly people will think of him due to his appearance. He’s definitely one of the best “shock value” artists of all time. He overdid it with that pig blood thing though.

LikeLike

There’s this song called “You Suck” and it’s basically a diss track about a boyfriend. It has at least 3 times as many dislikes as likes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgW7JMUipXg

This sure provoked a lot of people.

LikeLike

I’m gonna be very honest, I was genuinely afraid of this topic being discussed as this really is such a sensitive subject that can quickly get people defensive and heated (me included lol) but I do think in terms of “violent music” besides the societal push to declare music genres such as rap and heavy metal as the main culprits, I can only think of nationalist music that are made to contain subliminal hate rhetoric as the only form of actually morally bad music. Before you ask, yes unfortunately, nazi music is a thing.

LikeLike

The war music always has violence. The musician or composers makes a piece for the soldiers or the people of the country. When there was war going on in my country which ended in 1975, there was a lot of music came out for the war , some of them were made by foreigners too. Music expresses the feeling and tell the world about what’s going on so everyone know about it. And some music also carries some bad feeling about ending everything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Talking about this reminds me of what I had to do last semester in my English 102 class. We had to read a poem on war and associate music with it. Looking at Christen’s initial response mad me think of trumpets, and percussions, etc.

LikeLike

I think music is a form of expressing strong emotions or to give a message to people. Music could be violent, sad, happy or even indirect. Any type of music has a meaning. Just like how there’s the national anthems and songs made about the war, there are other songs which are made to inform people about the growth of the country or like to form unity. In my opinion, i don’t think there’s really a thing called violent music but there’s music or lyrics which are strongly expressed to make awareness or to simply display emotions to understand the seriousness of the situation. For instance, the erl king. It may sound harsh for the dad’s part because the father thinks there’s nothing but the son, the music displays anxiousness to show that he’s scared.

LikeLike

To add on the Dr. Jones final thought on music and censorship I have an example. If we pay attention to meaningful and powerful songs we get that feeling of inspiration. All of that is censorship. We are receive the idea of what the composer of the song wants to get off.

LikeLike

I think music is a great way to express political views, express feelings of violence rather than acting on them. America has been very violent since Donald trump became elected president and reading this reminded me there are peaceful ways to get a message across to someone, like music, for example.

LikeLike